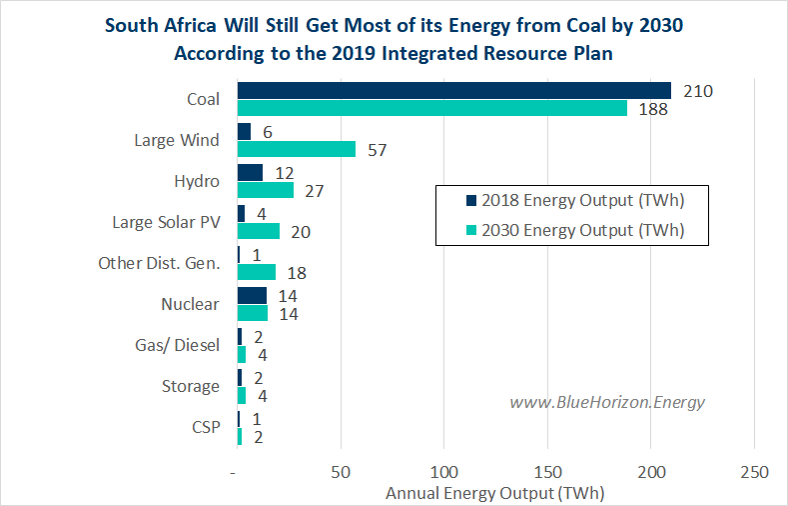

South Africa’s government finally published its national Integrated Resource Plan (IRP 2019) last week, which outlines the electricity plan for the country for the next 10 years. While renewable energy accounts for the majority of new capacity to be built by 2030, the plan lacks ambition in phasing-out coal faster to optimize economic, environmental, and social development goals for the country. Fortunately, challenges with financing new coal projects may make their inclusion in the plan irrelevant.

Key Changes in the Energy Plan

A number of revisions were made to the IRP2019 compared to the draft published in October 2018. On the plus side, wind has the most allocated new capacity of 14GW followed by utility-scale solar PV at 6GW, and will account for about a quarter of the energy generated by 2030 under the new plan. Like the 2018 draft, the IRP 2019 still contains annual build limits on new solar and wind sectors to allow for a “balanced” mix of new projects rather than a “least-cost” mix. Distributed generation for projects <10MW will be uncapped until 2022 to meet near-term supply shortages with 500MW/yr of distributed generation larger than 1 MW planned going forward. The IRP 2019 also sees the benefits of increasing storage capacity by 2GW before 2030.

Nuclear over the next 10 years appears to be limited to a retrofit of South Africa’s existing 1.9GW Koeberg nuclear plant to extend its life for another 20 years beyond 2024, but the cost assumptions for the retrofit remain unclear. Gas and diesel capacity has been reduced from the 2018 draft from 8.1GW to 3GW due to gas availability and locational issues cited.

Subsidizing New Coal With a “Balanced” Energy Mix

Despite growth in renewables, distributed generation, and storage, coal will still provide the majority of South Africa’s energy (~60%) by 2030. In addition to finishing the delayed and overbudget Kusile coal project, the IRP allocates 1.5GW of new and more expensive coal to be built which would likely include the Thabametsi (577 MW) and Khanyisa (300 MW) coal plants if they can secure financing. Many international and local banks in South Africa have taken a responsible investment approach and now refuse to finance new coal plants due to their associated risks with climate change, however China’s development finance institution (DFI) has been earmarked to potentially fund Khanyisa.

The conflicting priorities in the IRP 2019 of a “least-cost” and “balanced” mix shows that government can’t have both if it wants to build new coal projects, so is in effect subsidizing the development of coal plants if these projects were to go ahead.

Climate Finance can Unlock Renewable Energy Benefits

Recent studies like LUT University’s ‘Pathway towards achieving 100% renewable electricity by 2050 for South Africa’ have already shown that a renewable energy focused mix would be less expensive, eliminate emissions, save water, and create more jobs in South Africa. The net benefits for the country are clear, but the energy transition requires the political support to make it a reality. South Africa has a well-established coal sector which continues to oppose the clean energy transition despite the net benefits for the country, suggesting that more work to get buy-in for the Just Transition is required to phase-out coal faster.

Climate change financing solutions have attracted interest from DFI’s and impact investors like the R200 Billion climate financing vehicle to assist Eskom with its growing debt under concessionary terms that the utility proceed with unbundling reforms and old coal plants be phased out faster to meet emission goals.

Government has fortunately acknowledged that the IRP is a ‘living plan’ which will need to adapt to changing costs, technology advancements, and customer demand in the coming years.

More Supply Shortages Creating Opportunity for Renewable Energy

South Africa began loadshedding again last week due to a shortage of supply and outages at a number of Eskom plants including the newly built Medupi coal plant and means the utility is still burning expensive diesel during peak periods to keep the lights on. Hopefully this further incentivizes the regulator to approve distributed generation projects with a pending license application quickly. The business case for distributed generation will also continue to improve with another rate increase request from Eskom. The market size for new distributed generation in South Africa ranges from 6-7 GW in the next 10 years. The utility-scale market size is much larger and with the IRP 2019 finalized, there shouldn’t be any major hurdles preventing government from beginning Round 5 of the Renewable Energy Independent Power Producer Procurement Programme (REIPPPP) as soon as possible to avoid future supply shortages.

While the IRP 2019 isn’t perfect, it is a positive sign that the electricity industry can begin moving forward again with a working roadmap.